STORY SNAPSHOT

- Jimmy Doolittle was born in the 19th century. He became a military aviator in the 20th century. He was also an aeronautical engineer. He earned a doctorate in aeronautics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1925.

- He is an inspiration for all in the 21st century.

- As an aviator, he was the first pilot to fly a plane for its entire flight with just instruments. He did this in 1929. He retired from active duty in the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1930.

- But as World War II erupted, Doolittle served again in the military.

- In April 1942, he led the Doolittle Raid on Tokyo. Twenty B-25 bombers took off from the USS Hornet, an aircraft carrier. Pilots and crew knew they would not have enough gas to return to the carrier. The raid was America’s response to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

- For his actions, Doolittle was given the Medal of Honor and promoted to General.

- On D-Day, Doolittle flew over the beaches after the initial assault and reported to Gen. Eisenhower. His report was the first air intelligence Eisenhower received that day.

- Gen. Doolittle wrote his autobiography in 1991. Upon reflecting on his life, he said he could never be so lucky again because the girl he loved married him. And he loved his aviation career.

May 4, 2020 – Gen. James “Jimmy” Doolittle was born in the 19th century, excelled as a military aviator in the 20th century, and serves as an inspiration in the 21st century. For a glimpse into his remarkable life, read his autobiography – I Could Never Be So Lucky Again.

Published in 1991 when he was 95-years-old, his autobiography tells his uniquely American story of hardscrabble times yet his determination to succeed. His life ran in parallel to man’s quest to conquer human flight. But he was also firmly grounded on Earth with a principled character, unbridled curiosity, and superior problem solving skills.

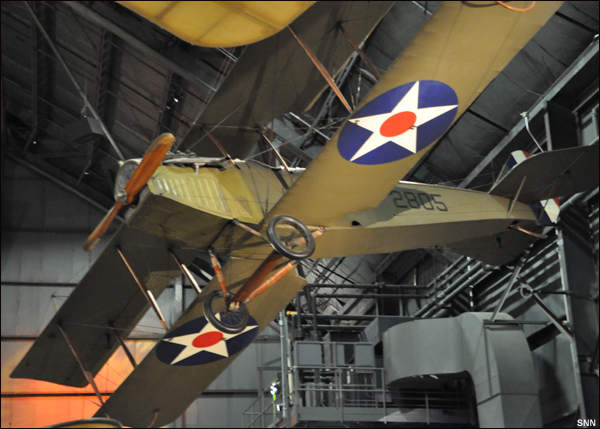

In 1903 when Orville and Wilbur Wright first flew a heavier-than-air, human-powered machine on the shores of the Atlantic Ocean in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, Jimmy Doolittle was a young boy living in Nome, Alaska. His family had moved to Alaska from California during the Yukon Gold Rush. It was here Jimmy naturally acquired street smarts.

Doolittle’s mother returned to California with Jimmy so he could receive a better education as he approached his high school years. In 1910 at age 13, he was introduced to aviation when he attended an air meet at a field outside of Los Angeles. Glenn Curtiss, famous pilot and airplane manufacturer, was there. Doolittle marveled at the different designs of airplanes that all stayed in the air. What were the principles of aeronautics, he pondered.

Two years later he tried building his own glider but could never get it airborne. He again pondered the principles of flight.

As World War I (1914-1918) broke out, Jimmy joined the aviation section of the U.S. Army Signal Corps. The Army sent him to ground and flight school. He flew his first solo flight after flying with an instructor in the plane for a total of seven hours and four minutes. (I Could Never Be So Lucky Again, p. 39) He was learning the principles of aeronautics.

“The basic reason for most crashes in the early days was because a student stalled the plane and got into a spin. At first, none of us knew why airplanes got into spins or what to do to get out of them. Later, we learned why they happened and how to recover from them. Stall and spin recoveries became a vital part of all flight curricula.” (p. 40)

Jimmy graduated from flight school on March 5, 1918 and remained stateside as a flight instructor until the war ended in 1918.

Doolittle excelled in the air and in the classroom. He was one of the first students in the country to earn a doctor of science in aeronautical sciences from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1925. He credits his wife, Josephine “Joe,” for helping him earn his degree. While caring for two small boys, she would type all of his notes from class to make the material easier to study.

For his master’s degree in 1924, Doolittle wrote a thesis titled, “Wing Loads as Determined by the Accelerometer.” It was based on hours flying airplanes to test aeronautical principles. Based on his thesis, he wrote another paper for the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics (NACA), the predecessor to NASA. Orville Wright was a founding member of NACA.

For his dissertation to earn his doctorate, Doolittle researched wind velocity, an area of disagreement among experienced pilots of the day. His topic – The Effects of the Wind Velocity Gradient on Airplane Performance – was approved. He graduated in 1925.

Because Doolittle understood aeronautics so well, risks he took in the air that made him appear a daredevil were in fact, just the opposite. Doolittle took calculated risks to advance the science of aviation. One of his greatest contributions to aviation was the addition of instruments in the cockpit. Doolittle realized early on that pilots needed to be able to fly in all kinds of weather conditions so they would not have to only rely on visual cues. In 1929, he was the first pilot to fly a plane solely by instruments.

In 1930, he retired from active duty military service and went to work for Shell Oil Company in charge of their aviation department. He joined the Army Air Reserve Corps.

The 1930s were fascinating years in Doolittle’s career as he traveled to Germany on Shell business. He met Ernst Udet, a World War I German ace pilot, second only to the famous Red Baron (Manfred von Richthofen). Udet had traveled to America in 1933 to purchase two, Curtiss-Wright Hawks for the German government. Later he demonstrated the airplane to the Luftwaffe, Germany’s air force.

“It occurred to me much later that this purchase of two planes was part of the Nazi master plan to procure our best pursuit planes and have them analyzed by their engineers. It is said that the famous Stuka dive bomber design was developed from ideas derived from the Hawk.” (p. 192)

In summer 1939, Doolittle was in Frankfurt, Germany on Shell business. He became increasingly uneasy at what he saw. Soldiers in Nazi uniforms were everywhere. Udet was now a director in the German Air Ministry and his carefree nature had changed dramatically. Doolittle met a few German pilots.

“They talked openly of war in Europe as being inevitable and wanted to know what America would do about it when it came. Their arrogance was irritating.” (p. 195)

Doolittle returned to America via London in August 1939. He went straight to see Gen. Hap Arnold, chief of the U.S. Army Air Corps.

“I told Hap I was totally convinced that war was inevitable, that the United States would be involved in hostilities, and that we would be unable to remain aloof from whatever happened in Europe. I was so sure of it, in fact, I told him I was willing to give up my job with Shell and serve full time or part time, in uniform or not, in any way he thought would be useful.” (p. 196)

Two weeks later on Sept. 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland and annexed 36,000 square miles of the formerly sovereign country. The war so many Americans wanted to avoid had started.

Doolittle left Shell and reported for active duty on July 1, 1940. He was 43-years-old. His expertise and experience were invaluable to the Army Air Corps as America prepared for the likelihood it would be drawn into war in Europe.

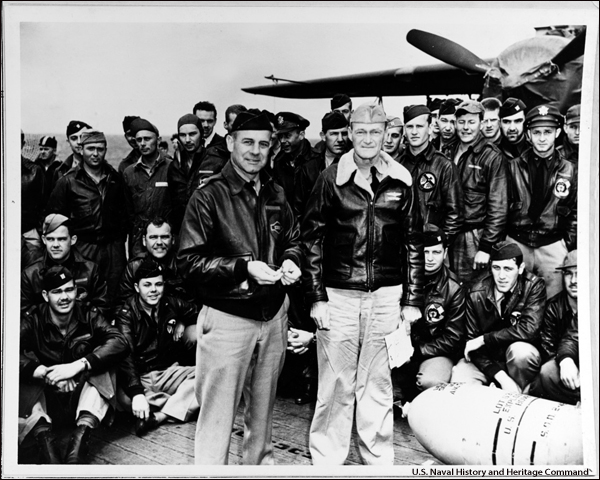

Doolittle Raiders – April 18, 1942

After Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Gen. Arnold tapped Doolittle to plan a strike against Japan in retaliation for the Pearl Harbor attack during which more than 2,000 soldiers and sailors had been killed and about one-half of America’s Pacific fleet damaged or destroyed.

On April 18, 1942 from the USS Hornet, an aircraft carrier, 16 B-25 bombers, each with a crew of five with Doolittle in the lead, took off knowing they would most likely run out of gas before their planned landing in China. There was no way they could make it back to the carrier.

Every B-25 crashed landed after the raid over Tokyo. The raid showed Japan that the United States could reach its soil. While the raid itself did not do a lot of damage, it was very important to the course of the war as Japan shifted their resources to defend the homeland.

Doolittle was awarded the Medal of Honor and promoted to Brigadier General.

In January 1944, Doolittle was put in charge of the Eighth Air Force stationed in England. His mission was to ensure the German Luftwaffe would not be a major factor during the Allied invasion along the Normandy, France coast planned for that spring.

On D-Day, Doolittle flew reconnaissance over the beaches. He reported to Gen. Eisenhower that the Luftwaffe was unable to put up a major defense from the air. Their mission had been accomplished.

Gen. Doolittle returned to civilian life but continued to serve his country.

At the end of his autobiography that he penned in 1991 with Carroll V. Glines, Gen. Doolittle articulated his life philosophy, an inspiring message for the 21st century.

“One of the privileges of age is the opportunity to sit back and ponder what you’ve seen and done over the years. In my nine-plus decades, I’ve formed some views about life and living that I have freely imposed on trusting audiences, both readers and listeners. I have concluded that we were all put on this earth for a purpose. That purpose is to make it, within our capabilities, a better in which to live. We can do this by painting a picture, writing a poem, building a bridge, protecting the environment, combating prejudice and injustice, providing help to those in need, and in thousands of other ways. The criterion is this: If a man leaves the earth a better place than he found it, then his life has been worthwhile.” (p. 501)

Gen. Doolittle also reflected on what had been important to him personally.

“Luck has been with me all my life. Fortunately, I was always able to exploit that luck in my flying years and at every turn in my career. The best thing I ever did was to convince Joe that she should marry me; the luckiest thing that ever happened to me was when she finally did. That’s why, whenever I’m asked, I say that I would never want to relive my life. I could never be so lucky again. Thanks Joe, I couldn’t have done it without you.” (p. 502)

Joe passed away in 1988 and Gen. Doolittle died in 1993. They are buried side-by-side at Arlington National Cemetery.

Author’s note: This article is the anchor article in Lesson Plan #6: Technology and Heroes in the Cockpit. Video included is from my 2014 interview with Jonna Doolittle Hoppes, Gen. Doolittle’s granddaughter.

Another article included in this lesson plan is a profile of Lt. Col. David Hamilton, the sole surviving WWII Pathfinder pilot. Included is a video from a May 2019 interview before he left in a C-47 to cross the Atlantic to commemorate the 75th anniversary of D-Day.

Finally, the story of Vito and Geraldine “Jerry” Pedone is amazing. Vito was the co-pilot in the lead Pathfinder C-47 (first of 20) on D-Day. Jerry Pedone, his wife, was an Army flight nurse on C-47 flights that began four days after D-Day to bring wounded soldiers back to British hospitals. Their story is told on this website in Part 1 and Part 2. Many thanks to Lt. Col. Stephen Pedone (USAF Ret.), their son, for photos and information.

Vocabulary

- excelled: (verb) – performed very well and at a high level

- aviator: noun) – a person who can fly a plane or helicopter

- inspiration: (noun) – something that inspires, motivates

- glimpse: (noun) – snapshot, a small or partial look at something

- remarkable: (adj.) – amazing, noteworthy

- autobiography: (noun) – a book written by a person about his or her life

- uniquely: (adverb) – one of a kind

- hardscrabble: (adj.) – difficult, not easy

- determination: (noun) – perseverance, state of being determined or committed

- unbridled: (adj.) – without limits or constraints, endless, boundless

- curiosity: (noun) – state of being curious, inquisitive, asking questions to find answers

- stature: (noun) – height

- aeronautics: (noun) – the study of the principles of flight

- pondered: (verb) – thought about

- instructor: (noun) – teacher

- aeronautical: (adj.) – related to aeronautics, the study of flight

- accelerometer: (noun) – an instrument to measure acceleration, increase in speed

- predecessor: (noun) – one who came before

- dissertation: (noun) – research paper submitted to earn an advanced degree

- velocity: (noun) – speed

- procure: (verb) -obtain, usually through buying; get; acquire

- analyzed: (verb) – studied carefully to draw conclusions

- increasingly: (adverb) – growing or increasing to some degree of quantity or quality

- carefree: (adj.) – not serious or concerned about anything; free; fun loving

- dramatically: (adverb) – significantly

- inevitable: (adj.) – sure to happen at some point

- arrogance: (noun) – confidence that is not warranted or not appropriate

- irritating: (adj.) – annoying

- hostilities: (noun) – conflicts, combat, war, fighting

- aloof: (adj.) – not engaged, not easy to talk with

- invaluable: (adj.) – having great value

- likelihood: (noun) – chance something might happen

Review Questions

- What did Gen. Doolittle study at MIT where he earned two graduate degrees in aeronautical sciences?

- When did Doolittle learn to fly?

- What major event during World War II did Doolittle lead?

Inquiry Questions

- Cite evidence in the story that Gen. Doolittle achieved at the top level in both aviation and academics.

- How did Gen. Doolittle’s curiosity help him during his career?

- Is Gen. Doolittle’s philosophy of life relevant in the 21st century? [/restrict]